The only extant Mme. Demorest Running-Stich Sewing Machine which is based on William G. Cook's Patent of June 16, 1863. Sold!

Patents, click on any image to see larger image!

This is without any doubt, the only extant machine manufactured by Mme. Demorest, 473 Broadway, New York, N.Y., which is based on William G. Cook’s Patent of June 16, 1863. Mme. Demorest is know for her simple running stitch machines which are based on an earlier patent, Palmer’s Patent of May 13, 1862.

The earlier, very simple, running stitch machine had some success. While scarce, machines based on Palmer’s patent are to be found in many high-end collections.

The disadvantage of running-stitch machines was the need to remove the needle from the machine each time the crimping gears had pushed fabric onto the needle to its capacity. The needle used on running stitch machines was just an ordinary needle.

Cook’s Patent was an attempt to improve the running-stitch machines by eliminating the frequent need to remove the needle. Cook devised a complicatet mechanism to achieve this. On page one of his Patent specifications, Cook stated:

“Its object is to avoid the necessity of stopping the machine and taking out the work when a certain length has been performed, which is so great an objection to other machines of this class, and render continuous the stitching of a piece of cloth of any length.”Cook”s attempt to eliminate the drawback of the constantly needed interaction with the machine however was a failure. Examining this machine, I noticed that there is too much friction to achieve a smooth operation. The brass gears also are to soft and the gears are slightly bent from operating the machine. Using brass instead of steel added to the machine’s poor performance. Hence, it is not surprising that the existence of this version of the Madame. Demorest was unknown to collectors and also to Grace Rogers Cooper, former curator of Textiles at the Museum of History and Technology of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C.

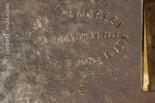

Grace Rogers Cooper is also the author of the book, ”The Invention of the Sewing Machine.” In her book, Cooper included a list of all the patent models in the museum. While there is a patent with the date June 16, 1863, patent number 38931, in that list, that patent has nothing to do with a running stitch machine. The date of June 16, 1863, stamped into the stitch-plate of this machine was a mystery at first. I went through all the patents issue on this date and found another patent issued on the same date of which I posted images above. This second patent has the number 38,927 and was issued to William G. Cook of New York, N.Y.

This exceedingly rare, and at this time the only extant example, clamps on a table and measures 8 inches wide, by 4½ inches deep, and 6 inches in height. The flywheel measures 3⅜ inches in diameter. I do not even attempt to describe its function; please refer to the patent specifications shown above for your conveniance.

Condition:

The machine is complete; the patent specifications mention gutta percha, or Indian rubber pieces which obviously deteriorated over the last 160 years. Everything moves and nothing is frozen. The stitch plate has some rust spots. Most of the gilt is still on the frame of the machine and the flywheel.

As you may know, the earlier Madame Demorest machines with the simple design based on Palmer’s patent of 1862 are also entirely covered with gilt. I have not played around with this machine and I assume that it will be difficult to actually sew with this machine. The low serial number of 85 stamped into the stitch plate and the fact that this machine is the only extant machine, gives testimony to the fact that it did not work and was a failure. Hence, failures, it is exceedingly rare and for that reason, one of the most thought after example by collectors.

History:

Madame Demorest was a dress maker with location of, 473 Broadway, New York, N.Y., which also sold, among other things, running-stitch and other sewing machines to its customers. The earlier small machines could be easily carried around by seamstresses. Running-stitch machines had some success in the 1860's for that reason and because they were inexpensive.

Madam Demorest (Mme. Demorest) pioneered the art of putting dressmaking — and fashionable clothes — in the hands of all women. Mme Demorest was born to a “well to do” upstate family in 1824. At the age of 18 (in 1842), Ellen Louise Curtis, so her maiden name, decided to open her own millinery shop in her home town of Schuylerville in the state of New York. At an early age, Ellen Louise Curtis was impressed by the fancy head dresses of well to do ladies and decided to become a millner, or ladies' hat maker.

Her shop was a great success and after a few years (in the 1850s), Nell, as she was known, moved to New York City, where she continued to do well. One day she noticed that her maid was cutting rudimentary dress patterns from crude brown wrapping paper. All at once the idea hit her: why not print such patterns on tissue paper, which was far cheaper and could be replicated and distributed endlessly at low cost?

Meanwhile Nell had met a young widower named William Jennings Demorest, a dry goods merchant and promoter and, like her, from upstate New York. On April 15, 1858, the two were married. Demorest was already operating a store called Madame Demorest's Emporium of Fashion at 375 Broadway, just south of White Street. The newly wed decided that she should from now on be known for trade purposes as "Mme. Demorest."

Then Demorest had another scheme. Needing a vehicle with which to advertise Nell’s patterns, in 1860 he began publishing a quarterly magazine called Mme. Demorest's Mirror of Fashion that meticulously described Nell's designs and even included a sample pattern stapled inside it. The magazine proved highly popular and soon was selling throughout the U.S. and abroad; within a decade the Demorests had some 1,500 agencies, or merchandising branches, and were selling 3 million patterns a year.

The patterns were inexpensive — those for blouses went for 18 cents, while dresses “elegantly trimmed” were $1 and infants ' patterns sold for 12 cents apiece — and were constantly changing, as Nell was keenly aware that the fashion market demanded up-to-the-minute styles. Not only did she and her sister Kate (who had become her chief stylist) keep improving and changing their product, but each year Nell would travel to London and Paris to pick up the latest trends and would send notes back to Kate who would produce new patterns for their eager customers.

Competitors admitted she led the field. Wrote one rival, "What Madame Demorest says is supreme law in the fashion realm of this country."

One successful innovation was a small hoop-skirt that was an acceptable and far more manageable alternative to the otherwise popular full hoop-skirt. For customers unwilling to give up the full hoop Nell devised what she called the Imperial dress-elevator, an arrangement of weighted strings that enabled the wearer to lift up a corner of the hoop to prevent it from dipping in the gutter.

And all the time Nell was supervising her successful business she was helping to expand opportunities for women. She hired white and black women on equal terms, founded an early women's club and served as treasurer of the New York Medical College for Women.

Nell Demorest and her husband William Jennings Demorest also went into the manufacturing of simple and compact running-stitch sewing machines and sold an estimated 3'000 to 5'000 of the machines based on Palmer's patent of 1862 under the name Mme. Demorest. The machine offered here was supposed to be an improvement based on Cook's patent of 1863 but never really worked. The serial number of the machine offered here is 85. The fact that the machine did not work combined with the fact that no other example ever surfaced is a clear indication that very few, probably less than 200, were ever manufactured. As a matter of fact, the machine offered here and its patent with the number 38,927, issued on June 16, 1863, were unknown to major collectors until the discovery of this very machine. Grace Roger Cooper, in her book, "The Invention of the Sewing Machine," printed a list of all patent models in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution. The list is comprehensive and includes a patent issued on the same day, June 16, 1863, with the number 38,931. That patent however has nothing to do with the machine offered here as it is not a patent for a running stitch machine. Advertisements published in their magazines also offer Demorest velocipedes and later bicycles.

There was only one problem with the Demorests' glory ride. In all the rush to found a new business and keep innovating, the couple had never sought to patent Madame Demorest's methods.

But in 1863 a rival pioneer, one Ebenezer Butterick from Sterling, Mass., had independently developed his own system for producing paper patterns, and he had patented his methods. In the 1880s Nell and William found Butterick's business eating into their own and in 1887 they reluctantly decided to fold. They devoted their remaining years to worthy causes they had long espoused, such as temperance and women's suffrage. And so the Demorest business quietly expired, leaving the field to Ebenezer Butterick — whose firm, despite many name and ownership changes, exists to this day. To see the Butterick website, click here!

The Demorest Manufacturing Company was located in Williamsport Pennsylvania. By 1907, the manufacture of sewing machines and bicycles had become unprofitable for Demorest, and the company was sold and restructured as the Lycoming Foundry and Machine Company, shifting its focus towards automobile engine manufacture. Among the many different Car manufacturers buying engines from the company was the legendary Duesenberg J series. The engine for the Duesenberg produced 265 horsepower, six times the power of a contemporary Model A Ford. A supercharged version, generating 325 horsepower, was installed in the Duesenberg SJ and SSJ models. In 1929, Lycoming produced its first aviation engine, the nine-cylinder R-680 radial engine.

Lycoming Engines built more than 325,000 piston aircraft engines and powers more than half the world's general avaiation fleet, both rotary and fixed wing. Today, Lycoming is an operating division of Avco Corp, itself a subsidiary of Textron.

In 1889, a group of people from Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Ohio, and Indiana moved to Georgia to found a community which would have high moral standards. They decided that anyone who permitted drinking alcoholic beverages, gambling, or prostitution would forfeit their property. William Jennings Demorest formed the Demorest Home, Mining, and Improvement Company to make that dream a reality. On November 13, 1889, the town was incorporated and named "Demorest" in honor of the great Prohibition leader.

The Butterick camp stoutly claims it invented the paper pattern scheme. Don't believe it. The dates prove it: Nell Demorest was first. Nell Demorest died in 1898 at the age of 74.

Inventory Number 09331;

Price: Sold!