Leclanche Battery, Patented 1866. Sold!

Patents, click on any image to see larger image!

Rare find! An all original and early Leclanché battery; French Scientist Georges Lionel Leclanché is the inventor of the dry-cell battery. The battery offered here is in remarkable condition and still retains most of its original paper label, see picture 4.

Introduced by Georges Leclanché (1839-1882) in France in 1866, he also protected his invention with patents in the United States.

Even so Leclanché glass batteries or piles were sold by the thousands, their ephemeral nature makes them rare and hard to find today, especially the very early version. Occasionally an empty surviving glass jar is being identified as a glass jar of a Leclanché battery. The name LECLANCHE embossed on the jar is a give away and identification is easy.

The example here offered is the only early one I have ever seen with a paper label still attached to the glass jar. Furthermore, I could also not find another one on the internet with the original label, see picture 4.

The paper label reads as follows:

These glass jars were cleaned and re-used; today we call it “re-manufactured.”DIRECTIONS FOR SETTING UP

THE LECLANCHÉ BATTERY

1. Place the Glass Jar for Disques 6 ozs. of Sal Ammonia.

” ” ” ” ” No. 1, 3

” ” ” ” ” No. 2, 2

2. Rub on the inside of the upper rim of the Jar with Parafin

or ?????se, (to prevent the salts which are brined

from running over the edge of the Jar.)

3. Pour in water until the Jar is one-third full.

4. Stir up the mixture.

5. Insert the Porous Cell.

6. Fill with water to the shoulder of the Jar, and pour a

little of water in the hole in the Porous Cup.

7. Insert the Zinc.

8. Keep in dry place if possible.

9. See that the connections are clean, and that the wires of

the two poles are insulated or not touching.

10. Batetry [sic] should be set up, poles not connected,

twelve hours before use, in order that the solution

may saturate the contents of the Porous Cell.

11. Never put battery of different make in the same circuit.

12. As evaporation takes place replenish with water

and Sal Amonia.

The rest of the label is missing ..... Interesting here is that the label has a misspelled word, the word “Batetry.”

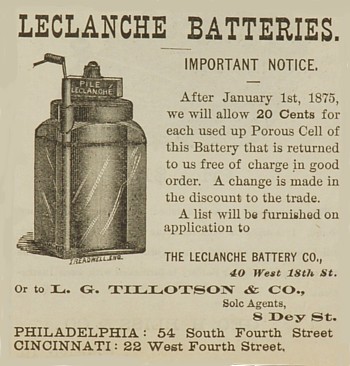

The advertisement on the left states, “After January 1st, 1875, we will allow 20 Cents for each Porous Cell of this Battery that is returned to us free of charge in good order.”

When used to power a telephone, the Leclanché battery gave a continuous current only for a short time after which the sound of the conversation would get weak forcing the callers to hang up. This is due to the accumulation of hydrogen bubbles, hence, the internal resistance increases and the drawn current decreases. Once the battery was disconnected by hanging up the phone, the battery would recover by itself, the bin-oxide gradually destroying the polarization, see [1], page 13.

Leclanché batteries lasted a long time and were used until the middle of the 20th century.

Condition:

The glass jar is perfect, no cracks or repairs. Everything is original, down to the wires the way they look in the picture of the advertisement shown on the left.

History:

Alessandro Volta (1745-1827) discovered that the combination of two distinct metals with moisture in between produced electricity. In a letter dated March 1800 to Joseph Banks (1743-1820 Scientist), Volta described his invention which is considered the first battery. His battery became known as the Voltaic pile. It consisted of a combination of cooper and zinc plates with cloth moistened by salt water as electrolyte to insulate the plate.

Two men's work became crucial in advancing battery technology after Volta’s discovery. The next in line was John Frederic Daniell (1790-1845) who devised the Zinc - Copper pile using for the first time a porous tube or cone.

The next in line was Leclanché with his Zinc-Carbon battery in 1867.

His first patent Leclanché was granted in the United States on June 5, 1866, with the number 55,441.

In this patent, Leclanché mentions for the first time the advantages of a Zinc-Carbon battery over earlier types of batteries.

Leclanché’s battery is composed of a zinc anode with a manganese dioxide cathode wrapped inside a porous material. The cell, considered a “primary” cell, made use of an ammonium chloride solution as the electrolyte. With carbon mixed into the manganese dioxide cathode; his battery presented faster absorption and longer shelf life. His first patent (no. 55,441) was re-issued on February 17, 1874 under the number 5,769

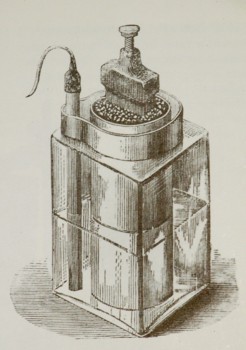

While most applications used the Leclanché Pile with liquid electrolyte inside a glass jar as shown in the picture on the right, Leclanché’s improved battery patent also suggested to substituted the liquid electrolyte with a pastier version, which resulted in the creation of the first dry cell battery. Such a battery could be used in different orientations and transported without spilling.

To see another item on this website which uses an open battery with liquid electrolyte and the problem such a setup creates,

click here!

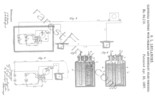

His second patent was granted on April 23, 1867, and was assigned the number 64,113, see pictures above. His first patent was re-issued on February 17, 1874, with the number 5,769.

These Leclanche Batteries were used in the forth quarter of the 19th century to power telegraphy and telephone equipment, therapeutic electric shock apparatus, electric fans, early electric motors, incandescence lighting, for electroplating, alarm and house bells, and many other applications.

The modern supermarket battery can be traced back to Georges Leclanché, a politically active French engineer and chemist, whose father was a lawyer prominent and political enough to fall foul of King Louis Philippe’s government in the year of the revolution, 1848. His mother was roughed up by the police a few days after the birth of Georges’ brother and died as a result. His father therefore fled to the more liberal England, in an age where it welcomed political dissidents of all kinds.

After completing his schooling, Georges returned to France in 1858. He studied engineering at the prestigious Ecole Centrale engineering school in Paris, graduating in 1860. He was then hired to develop a network of electric clocks for the recently established railway firm that linked Paris to Strasbourg. Dissatisfied with the power sources used by the firm, he began to explore alternatives. Then the political situation in France got hot again, and in 1863 he quit and moved to Bruxelles in Belgium, where he set up a small lab to develop his new cell.

Previous cells required two different electrolytes, typically separated by a porous barrier. Could one simplify the cell and use only a single liquid? Georges used zinc for the anode and chose manganese dioxide for the cathode because of its inertness and good electrical conductivity. As the manganese dioxide source he recommended using the mineral pyrolusite ‘fairly free of gangue’, taking care not to grind it too fine to maintain conductivity. He then added carbon as an electrically conducting support and pressed the mixture into a rod. For the electrolyte he tried many different alkali metal salts. None was satisfactory. But with concentrated ammonium chloride he obtained a steady voltage and a steady current, far superior to Daniell’s battery.

He found an investor in the electrical engineer and entrepreneur Charles Mourlon. With Georges’ brother Maurice they started making batteries that were soon in use in telegraphy and the silver electroplating business. With the fall of Napoleon III in 1870, the Leclanchés moved back to Paris, with Georges still tinkering and optimising his battery. In 1873, he added starch to the ammonium chloride solution. This gelatinised nicely, giving the required electrical conductivity and making the cell completely portable. The ‘dry cell’ was born.

Georges never lived to see the battery market really take off — he died of cancer in 1882. Leclanché cells would be the world’s leading battery until the acidic ammonium chloride was replaced with potassium hydroxide around 1900, quadrupling their capacity. Today the alkaline zinc/manganese battery can be found powering myriad everyday applications.

And yet there remains a fundamental flaw with these brilliant power sources; you use them once and then throw them away. With rechargeable batteries everywhere, why do we still allow this supremely simple, yet disposable, electrochemical tech in our electrified world?

For further study of batteries, I recommend [1] as the following types are described; Smee battery, the Grenet Battery, the Daniell battery, the Grove battery, the Bunsen battery, the Carbon battery, the Nickel-Plating battery, Fuller’s Mercury Bichromate battery, the Leclanche battery (pages 13-15), the Diamond Carbon battery, the Law battery, Gravity batteries, and dry batteries.

Literature:

(Click on any title to see the online version of the book or publication if there is one.)

[2]

Nineteenth-Century SCIENTIFIC INSTRUMENTS, by GERARD L’E. TURNER, page 197-198, (1983).

Inventory Number 09214;

Price: Sold!